While cookie-cutter crafts are great for building hand-eye coordination and bonding with children, it’s important to realize that students of all ages are capable of so much more if given the right tools and encouragement. I asked artists Maida Jaspersen and Bill Bukowski to discuss the pros and cons of teacher-directed, step-by-step art lessons, and give their advice for rounding out grade school teachers’ art curriculum.

Maida Jaspersen

Maida Jaspersen is an art student at Bethany Lutheran College who has experience with assisting with summer art camps and teaching private art lessons. After graduating this May she plans to move to Thailand to spread the gospel through art.

William Bukowski

Professor Emeritus Bill Bukowski taught art at Bethany Lutheran College for 33 years, emphasizing traditional techniques. He continues to travel, paint, and give art lectures.

Is there a place for step-by-step art lessons at the grade school level?

Maida Jaspersen:

I think that step-by-step projects can be a great starting point for kids’ (artists’) ideas; however, it’s important to remember that the momentum of the artist working is more important than producing a reproducible product. Let the artists use the steps as a jumping point, and encourage exploration! If they produce something completely different and surprising, congratulate them! They’ve successfully ventured beyond the fear of failure and into the excitement of the unknown!

William Bukowski:

I do think there is a place because it gets kids excited about drawing, and they can be successful. I always paired step-by-steps with actual perceptual drawing: looking at simple objects and drawing what you see, such as sticks, seeds, leaves, or apples and oranges.

I taught summer art camp at Bethany Lutheran College for 20 years, and I used step-by-step art every day. I designed them myself and usually based the images on popular cartoon characters. There are plenty of different levels of step-by-step and how-to-draw books, so the resources are available.

What are some strategies for encouraging creativity and self-expression in young artists?

Maida Jaspersen:

Prompt them and ask for their ideas. And then take those ideas seriously. Do not try to lead them to an answer, but join them on the journey.

William Bukowski:

I think a way of encouraging young artists is to let them explore what they like and eventually urge them to learn and use some advanced skills to make their expression better or more realized. Having good art tools is essential. Each student should have good brushes, colored pencils, good erasers, an art journal—either supplied by the school or part of their supply list. One can’t be a painter with a terrible brush. I personally don’t care for colored markers just because touch isn’t part of how to use them.

What advice do you have for building a solid grade school art curriculum?

Maida Jaspersen:

I’d encourage slowing down and asking so many questions. Art and exploration takes time and curiosity. “Noodle art” may be interesting for a while, but if the ultimate goal is to grow the minds of these young artists, they will soon need something different. Authorize them to make their own creative decisions. I think you will be blown away by their brilliance!

William Bukowski:

My wife was a grade school teacher and she used one bulletin board for “artist of the month.” Then each month one artist was featured with images of their art as well as some biographical facts. Sometimes art assignments can be paired with the artist at least one week of the month. I do like it when the art assignment can work with another subject, such as history/social studies, and integrated in the curriculum rather than just as a stand-alone late Friday afternoon activity.

Any resources that you can recommend for art teachers?

Maida Jaspersen:

Further articles exploring pros and cons of noodle art:

What are your thoughts on noodle art? When teaching a technique, how do you balance following instructions while allowing for creativity?

]]>How to teach art is a big topic that can definitely be broken down further in future articles. But here is a primer to point you in the right direction, based on advice from three WELS art teachers:

Lori Ehlke

Lori Ehlke is a WELS art educator and watercolorist who has experience teaching all ages and has an impressive library of art tutorial videos on YouTube. I asked her to speak about the grade school art teacher perspective.

Michael Wiechmann

Mike Wiechmann, a mixed media artist and painter, teaches at Minnesota Valley Lutheran High School and has been building up a curriculum called WELS Creatives for other WELS art teachers to benefit from. He provides the high school educator perspective for this article.

Jason Jaspersen

Jason Jaspersen a master artist who teaches at Bethany Lutheran College. His philosophical approach to life helps to develop his students into blossoming professional artists—especially those who apprentice with him in his Art Service program—and he was gracious enough to share his thoughts on teaching college art.

First of all, why is teaching art important?

…in grade school?

…in high school?

…in college?

[Share these points with your school administrators when they ask why the school needs an art program!]

What skills would you expect students to come in knowing, and what skills are most important for them to learn?

…in grade school?

“I hope students are able to do basic drawing, know their shapes and colors, and have an idea on how to use basic lines, shapes, and colors to portray an idea.” – Lori Ehlke

Of course, the qualities and characteristics of those lines, shapes, and colors are going to look different in a Kindergarten classroom versus an eighth grade classroom. As students grow and mature, they will enter the art class with increasing levels of hand-eye coordination and prior knowledge. A high quality art class will sequentially build on the skills they learned in previous years and adapt for students at higher or lower abilities. Having a scope and sequence, or list of what content is taught when, can help to make sure that skills are being taught in age-appropriate ways and revisited in future years to reinforce them.

But what should be taught in grade school art classes?

“An art program should help students use the elements of art and principles of design when creating artwork, should help students learn to express their ideas creatively, and should teach them problem solving skills in a visual way.” – Lori Ehlke

The elements of art and principles of design are the basic building blocks of art, codified in a way that is easily practiced in isolation. The exact order and number may differ depending on the curriculum, but art teachers agree that mastering these gives the artist full control over the expression of their art.

[Some textbooks that I (Holly) found useful in knowing how to approach teaching the elements and principles of art for the different grade levels are The Art Teacher’s Survival Guide for Elementary and Middle Schools by Helen D. Hume and ART is Fundamental: Teaching the Elements and Principles of Art in Elementary School by Eileen S. Prince, but there are plenty of other textbooks that cover creating a sequential art curriculum.]

…in high school?

Besides the elements and principles of art, there are a few more skills that Mike Weichmann is hoping that incoming freshman have. He and a team of other art educators have collaborated on a list of vocabulary and concepts to develop before high school which can be found at welscreatives.com/outcomes.

Most high schools have at least art fundamentals classes in drawing, painting, and/or ceramics. Through these electives, students can develop their skills in seeing correct proportions and expressing themselves. Jason Jaspersen, who taught art at MVL before Mike Weichmann, says that in these years the important thing is mileage, or producing as much art as possible—whether that’s manga, fashion design, or whatever else happens to catch their interest—to hone their technique. If they also develop their own artistic voice in an AP art class, that’s a bonus, but college will give them plenty of time to work on that.

Knowing which techniques to teach can be daunting, so Mike Wiechman and his colleagues have several excellent lessons that are ready to go for Fundamentals of Art, Drawing, Painting, Ceramics, Graphic Design, and AP Art classes on welscreatives.com under 9th-12th Grade.

…in college?

If students don’t have the foundations down yet, such as observational drawing skills, rudimentary painting, and ceramics, they should take the time to build those first. For example, they should be able to see the difference between what is in front of them and their drawing and self-correct, as well as recreate what they see in a value reduction painting, basically creating their own paint-by-numbers. Besides that, Jason Jaspersen says, “I want somebody who’s into it.” Student interest will carry students through frustrations and difficulty (though he admits that it tends to make them “a little buggy about somebody making you do something you don’t feel like doing”). By the time they graduate, Jason Jaspersen hopes that the students have developed a unique voice, with each student solving a prompt differently according to his or her own instincts and agendas. But again, “If you don’t have your grammar down, you can’t really write the poetry,” Jason says.

From a Christian standpoint, Jason would love for students to understand how their faith and creativity can work together. As Luther has been quoted as saying, that doesn’t mean that a cobbler has to put crosses on every shoe he makes. But God made the student an artist and expects stewardship of that gift, for them to invest in it and make it better. “That’s just vocation,” Jason says, “whether you make money at it or not.” While they are not obligated to make Christian art specifically, some students do feel that calling, such as the Bethany students who created Bible story artwork for WELS Multi-language Productions and Jason’s liturgical art apprenticeship program, Art Service.

What advice would you give to a first time art teacher?

…at a grade school?

…at a high school?

…at a college?

[Save these points for future reference!]

Anything else you would like to share with new art teachers?

Lori Ehlke:

I have a YouTube channel (Ehlke Art) with over 300 videos that many WELS teachers use to help teach art.

Cassie Stephens has written a book called Art Teacherin’ 101 and also has videos with art teacher tips.

Mike Weichmann:

My calling is to work with each individual student who comes into the art room to help them find and grow their gifts. What a blessing to get a chance to do this as my job.

I specifically have made a website, welscreatives.com, to be helpful to new art teachers or teachers in general. I am slowly building out the materials. Please use this as a tool, and when you make resources consider gifting it back to our creative community. On this website, I also have coloring pages, sketchbook prompts, banners for churches to rent, and various other questions I get from people. I love the idea of not creating barriers to students having good art lessons so all of these resources are free to use by teachers or parents.

Jason Jaspersen:

It’s crazy for me to be talking about this as if I know what I’m doing. I constantly feel like I’m starting.

I’m of the belief that that God has been preparing you for the moment that you’re in. So I find the resources I need all over the place.

I think you have to find a way that you organize your thoughts outside of your head. For me, I’ve used the Getting Things Done method inside of Trello. That’s been my go-to for tracking tasks or keeping ideas for the future. And I’ve been at it long enough that I can cycle those things and re-encounter my earlier thoughts. Google Drive would do that just as well, or a sketchbook or notebook. I think the biggest thing you can do is get your thoughts out of your head and filter through all of these resources so that you ingest the information, and when it comes out it sounds like it’s unified.

Being an art teacher can be very lonely. I experienced that on the high school level, because, you know, you’re the only one. I imagine at the grade school level too. If you’re the art teacher, well, what do people talk about at the lunch table? Probably not about museums or stretching canvas. At the college level, you probably have some peers, but not always. It depends on the scale of the program and the college. But I’ve heard artists described as border stalkers. Always looking at the boundaries, dwelling at the frontier of what if, maybe, and possibility. And a lot of people like to just hunker down in certainty. Most of the world likes that. Could be lonely out there at the frontier.

Maybe the last thing I would want to say is that it’s easy to feel insufficient, to feel a little ashamed that you’re not Super Prof. That happens to me. And somehow, I’ve recently shed that feeling this year; I’ve kind of dropped it and realized, God put me here. On purpose. Because ultimately, it’s in God’s plan. And also, from a surface standpoint, I’m hired. They chose me. And so I feel I feel more confident this year to assert that the things that are peculiar about me aren’t the things I should be hiding. They’re actually the reason I’m here. And that’s true for for other people, too. It’s hard to accept sometimes that you’re different on purpose. And it’s just right. Just right.

What other advice would you give to art teachers? Share in the comments!

]]>In the spring of 2023, Bethany alumnus and artist Charis Carmichael Braun was recruited to teach the Art History III: Modernism course at Bethany Lutheran College–from all the way in New York. Professor Braun used a wide variety of resources to give students a rich learning environment without a physical classroom.

Professor Braun started the semester with one-on-one Zoom calls with the students to get to know them. Later in the semester she had open office hours for Zoom check-ins with the students to see how they were getting along. If students had questions, they could either reach out to her individually or post to a public Questions forum on Moodle if it was something that other students could benefit as well.

The students purchased a subscription to Pearson’s online textbook copy of H. H. Arnason’s History of Modern Art. The e-textbook has tools for highlights, notes, and flashcards. It also in theory has an audiobook function, but the robotic voice is hard to listen to. So, in order to make reading the content more engaging, Professor Braun decided to record her own readings of the text, interspersed with expansions and applications. She made these videos available on her YouTube channel:

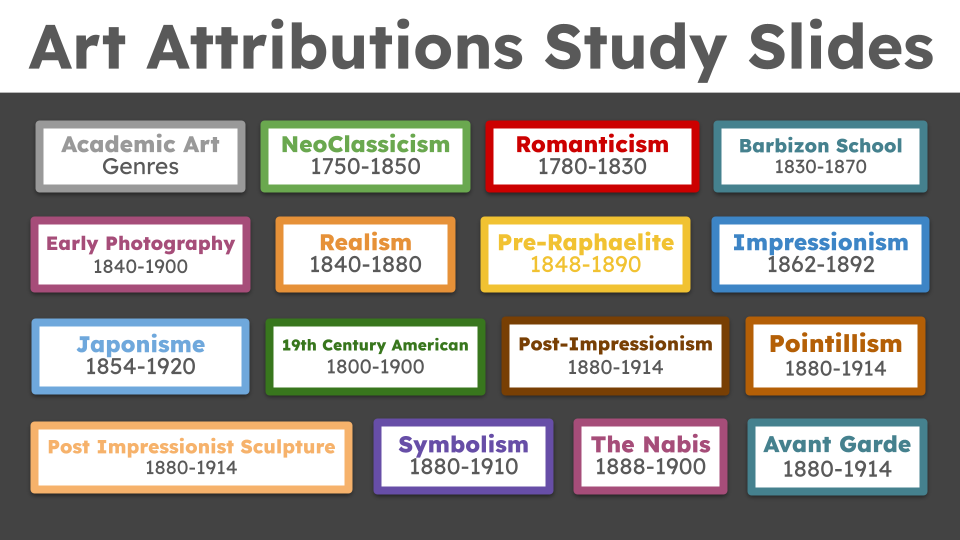

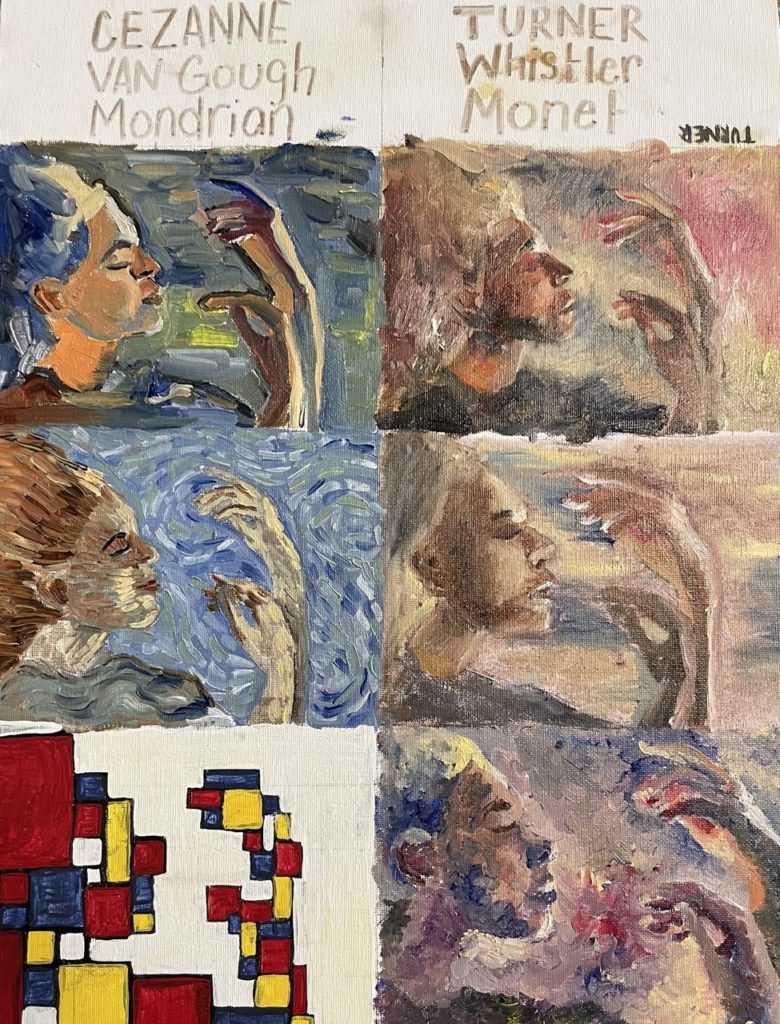

Periodically, the class would have an art attribution quiz based on the artworks covered by the textbook/videos. Students needed to match the artist and art movement to the artwork using a word bank. Since there was a lot of ground to cover and not all of it was in order by art movement, I made a slideshow that specifically listed the names and art movements in the notes section, so that students could use the slides like flashcards to study:

The activities on Moodle were separated by DO assignments, which would be graded, and other categories of DISCOVER, LOOK, BONUS, and FUN, which weren’t graded but were encouraged for extensions and to show participation. These were mostly links to further resources on the topic. There were also some extra credit assignments for the Minneapolis Institute of Art field trip and lectures by professor emeritus Bukowski.

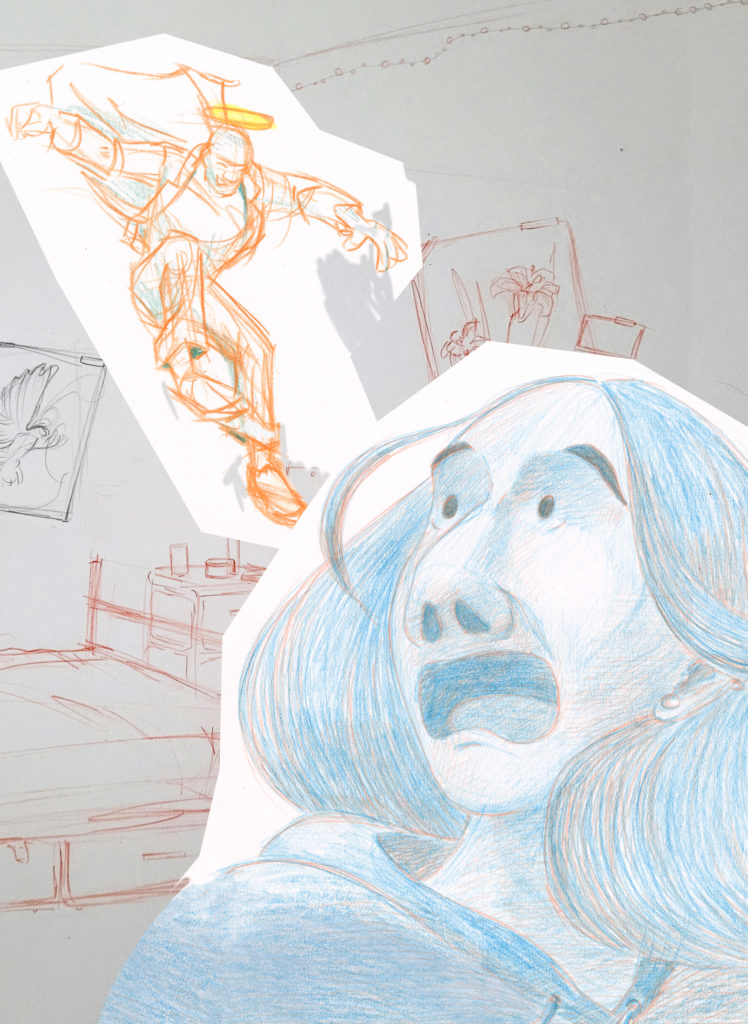

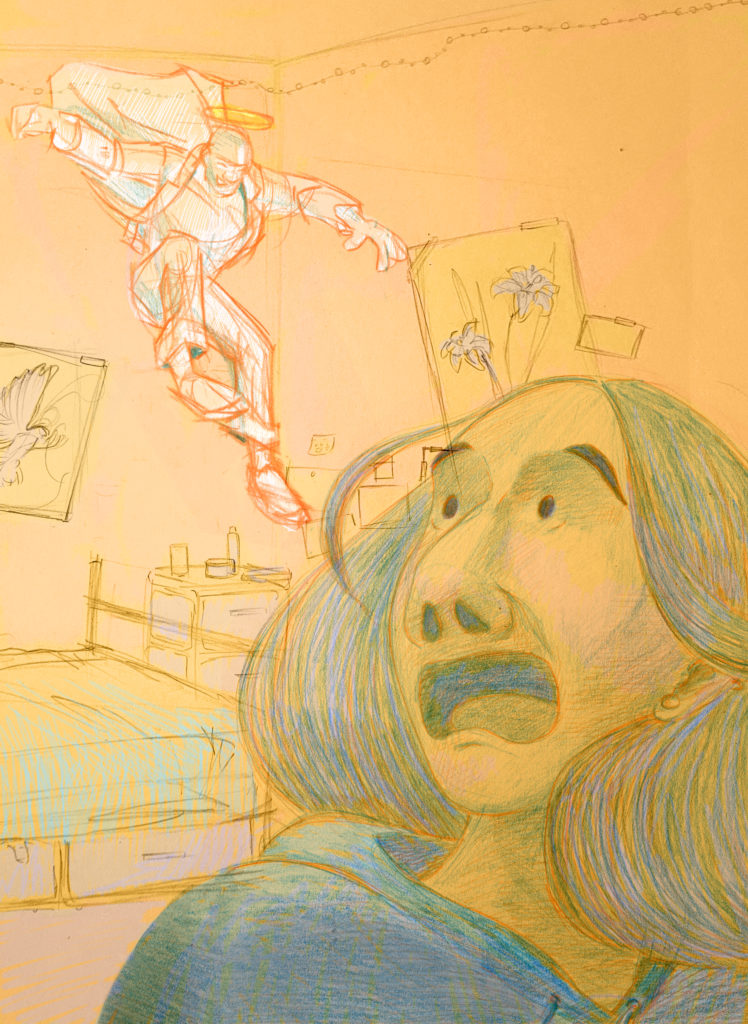

The DO assignments included deep discussion questions such as “Which holds more truth in it, painting or photography?” and the students’ chosen response to the weekly reading (inspired by Jason Jaspersen’s approach to art history assignments). Options for these responses could include a written summary, a master-copy of an artwork, a poem, a video, or some other project. Students also wrote essays reflecting on art lectures we attended at Bethany that semester.

As is often the case, there ended up being a lot of content left near the end of the semester, so to cover more ground Professor Braun had the students teach each other by creating their own slideshow on an art movement or artist. Here is mine:

Rather than dealing with the complications of setting up a way to present them to the class, the slideshows were posted as pdfs for students to peruse on their own time. They then had to respond to their peers with constructive feedback to show that they had read it.

In place of an exam, students worked on a cumulative paper or project summarizing what they had learned, such as the following:

This class was a goldmine of authentic experiences, despite being completely digital. I never felt unsupported or out of sync, because Professor Braun made an effort to get to know all of her students and promised to work with our schedules. The only challenging part was being self-motivated for the art lecture papers, which were due 5 days after attendance–but we could do them on any art lecture that semester, so it was easy to put it off until the next one. Overall, the pace of the course was manageable, and I felt like I came out of this course with a stronger knowledge of art history.

What tools have you found most useful for online learning?

How do you keep up student motivation for online classes?

]]>The first day of Art History II: Renaissance to Realism at Bethany Lutheran College, I and the other students were greeted not with a syllabus and a 7-pound Janson’s A History of Art, but with a letter.

Dear Art History student,

Writing a syllabus makes me grumpy and nervous. … So how about I write you a letter?

… There’s a lot to cover and we just won’t. Your life is complicated, my life is complicated, and the lives of great artists of the past were also complicated. That’s an important theme to consider. So we may or may not examine certain artworks in this semester, but no matter what, there will be mountains more to learn and understand.

… The artists we will study took their turn. They didn’t know that they were hundreds of years in the past. They were living in a sparkling present just like us. We study their work because they navigated through the obstacle course of every day and successfully pulled off some of the most moving, insightful, complex, layered reports of “being human” in recorded history. Generations have tested these artworks. Do they still feel true? It’s your turn to try them on for size.

… Will we cover the right stuff? Not sure. We might end up in surprising places. We might miss something important. We might find something really interesting. … We’ll learn about art history AND I think we’ll learn about how to find that information. It’s still a fantastic idea to buy “History of Art” by HW Janson, but I think you should by all the art books.

… I’ll entertain your suggestions. The whole point of quizzes, tests, papers, and projects is for you to assure the instructor that you weren’t sleeping. How would you like to express your understanding of art history? I thought about requiring everyone to create their own textbook. That’s still a great idea. You could write a great paper. … Would you consider learning fresco or egg tempera? I believe that people do their best work when they care about their work. So you tell me. When? How? Your call.

… Please don’t think I’m flippant about all this. I do take this seriously. I’m excited to engage in real exploration of this rich content with a group of one-of-a-kind individuals. My approach welcomes surprise twists and personalization. Customize your education!

Cordially,

Jason Jaspersen

Professor Jaspersen, who has a Master’s degree in Experiential Education, went on to say that traditional education is like a show dog–you’re preparing for a one-off performance of what you’ve learned. Their training is regimented and predictable. But project-based education is more like a stinky, mangy dog running wild, drinking the swamp water.

In that spirit, his vision for this class was that we would choose our own adventure for a final project. Every week we submitted portions of our project or progress reports, showing evidence that we had learned something from the lecture and discussion that week, all building up to our final project due exam week.

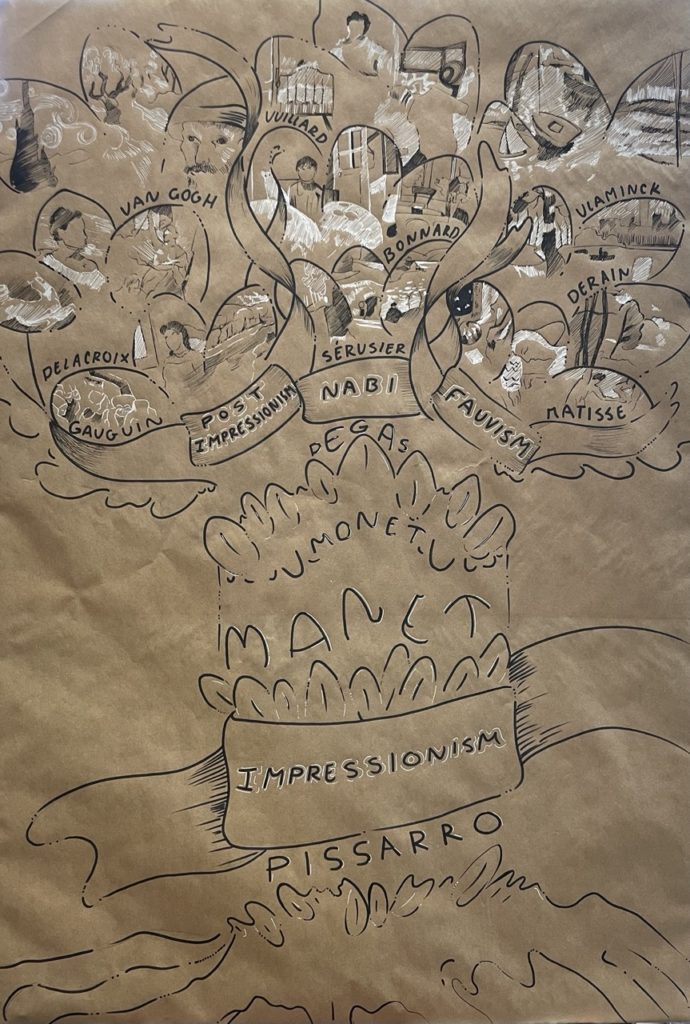

If there’s no textbook, how do you learn art history? For most days, Professor Jaspersen would put on a Prezi presentation on an artist from the era we were studying with very minimal words—just the name of the artist, some dates, and the titles of the artworks. He would zoom in close to the art, letting us absorb the details silently and then quietly ask us to shout out our observations. We had practiced the difference between formal analysis and narrative content to go from what we saw to what we interpreted, and by the end of the semester many of us grew more confident in speaking loud enough for the room to hear with whatever we noticed.

Professor Jaspersen would leapfrog from our observations to give us context on the artist and his era, expounding on the greater impact of these artworks. While there weren’t words projected and we weren’t going to be tested on these facts, we would often write down these pieces of wisdom to give direction to our projects or simply to absorb for our own information.

We didn’t just look at Prezi slides, either.

In the first few days, we made a field trip to the college library to do a library-sponsored scavenger hunt to learn how to scan shelves, and then we were assigned to find “The most beautiful art book in the library” and bring to class to talk about it.

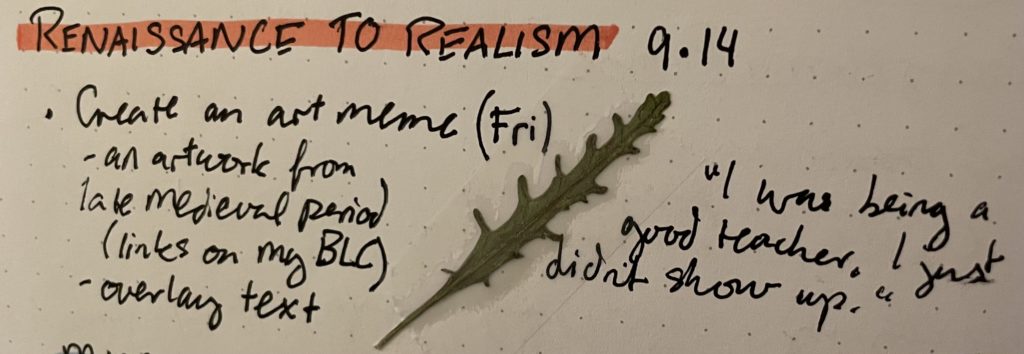

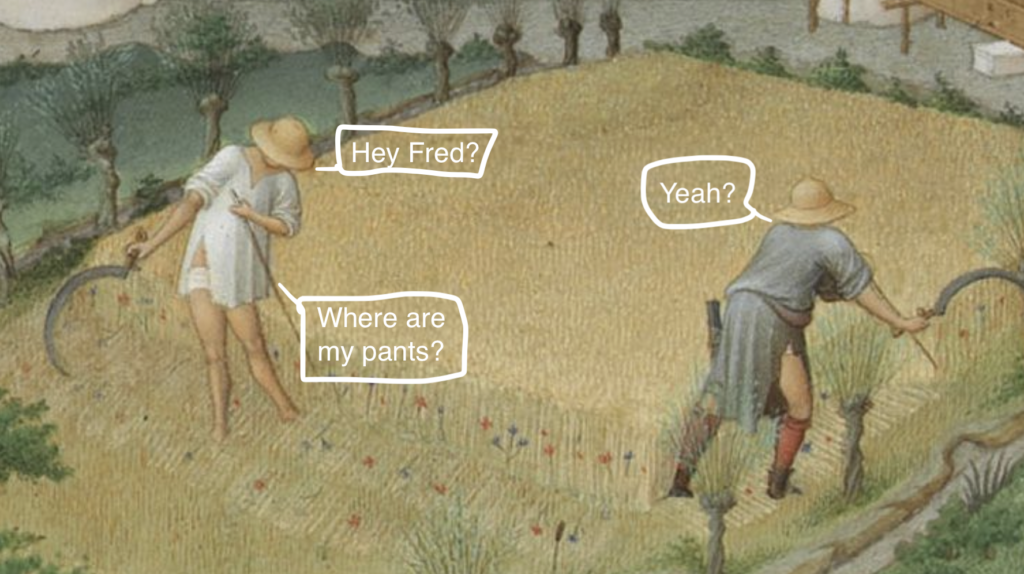

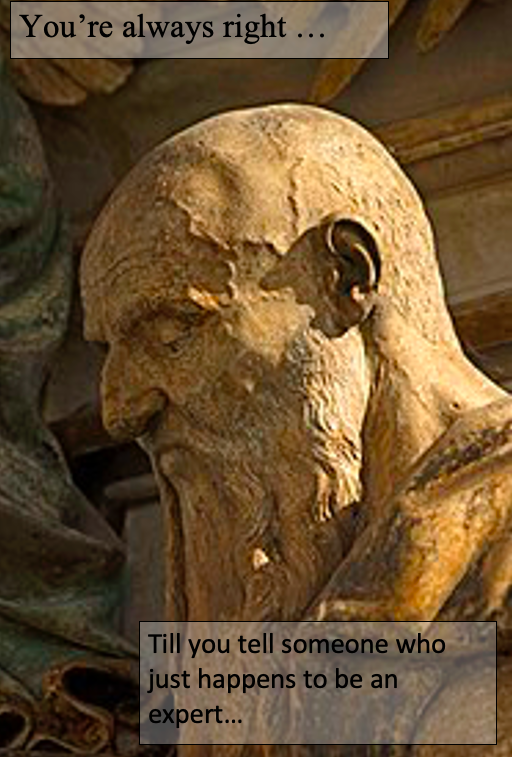

Another day we added to a class Jamboard slideshow, using different colored “sticky notes” to indicate formal observations, narrative content, and historical context. We also created art memes based on artworks we had studied.

We often looked at artworks in context through Google Earth, high resolution art museum scans, and SmartHistory videos. Though this year it didn’t work out to make it to the art museum in Minneapolis, we did do a tour of some of the artworks on campus.

When we checked in about how our final project was going, Professor Jaspersen would give us creative exit ticket prompts to write on index cards. One day we wrote our dreams for our projects in increasing scope, throwing our grandest ideas into the center as crumpled up balls that he would pick up and read anonymously.

Somewhere 3/4 in Professor Jaspersen confessed that he felt that we weren’t going to make it through all the content. He admitted that he was mostly trusting us to do our weekly assignments without following up as closely as he could have, because of his other responsibilities. One day he even waltzed in with sprigs of lavender half an hour after class started, saying, “I was being a good teacher–I was working on the art lecture. I just lost track of time and didn’t show up.”

But in the end it didn’t matter. We learned how to truly look at art, and applied what we had learned to projects that were personally interesting to us. We may have been guinea pigs to an experiential class, but that didn’t make what we had learned any less significant.

What are some nontraditional education methods you have used in the past?

]]>

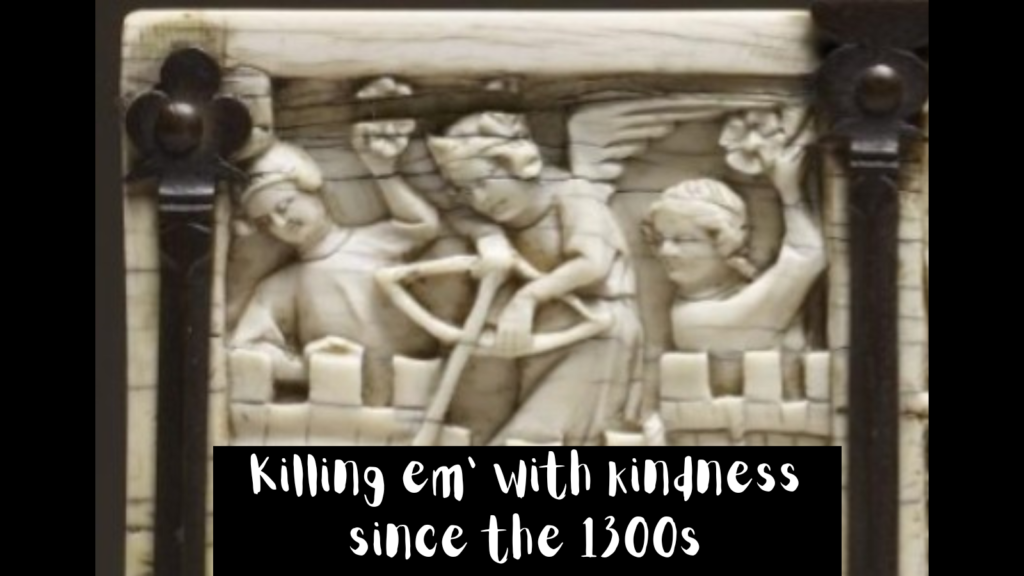

The Original Memes

Modern-day people love to bash the art of the Middle Ages for its awkward poses, inaccurate animal depictions, and strangely mature babies. This makes it great fodder for the Internet meme.

But if you look closer at Medieval art, they also enjoyed a good joke. Medieval humor tended to be about ridicule and the inversion of expectations.

The scene of Attack on the Castle of Love was so popular that it went viral in its own way: being carved on ivory mirror cases, caskets, and container lids. Women are shown defending a castle from men–but with roses instead of arrows. The romantic reversal imagery made the ivory trinkets perfect gifts for courtship.

Engaging with Artwork through Humor

One of the challenges of teaching art history is how to get students to really look at art, and how to measure and assess their discoveries. The irreverence of memes can provide a gateway for students to notice things in the artwork that they might not have seen otherwise. This can lead to discussions on artist choice and cultural context.

In Art History II at Bethany Lutheran College, Professor Jason Jaspersen had his students choose an artwork from the Late Medieval period to turn into a meme. Students could use whatever programs they wished; the only requirement was some sort of text overlay.

As we learned in that class, simply listening and taking notes isn’t enough—to truly learn something, you need to reflect, apply, reframe, or recreate the information. You can do that by explaining it to someone (The Phone Call), juxtaposing it with something else (The Mix), or creating something new inspired by it (The Replica). A meme would probably fall under The Mix, but you could also create a more informative textual overlay of the artwork.

This could be an opportunity to explore memes and Internet comics as an art form—it’s not unlikely that your digital artists may create webcomics someday, and it would be inspiring to explore how it has shaped our culture.

The concern may come up that students could uncover more disturbing images as they scour the Internet for cringe-y artwork, so depending on their level you may want to limit it to specific pieces or use an online gallery that you’ve already previewed.

It may also be a good idea for students to disclose which artwork they used in their meme, in case the class wants to look at the artwork in context. It’s also just good practice to cite the source, though memes and educational use generally can get by with using copyrighted images. If students are shy about sharing their memes (humor is a vulnerable thing to create and not everyone has the same sense of humor), you could display them anonymously with the class.

Any piece of art from any art period could lend itself to memes—but the more you meme an artwork, the less viewers are able to truly see it for itself. Famous artworks such as the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper especially suffer from this veil. For this reason I wouldn’t overuse this assignment, even though it’s easy to assign and grade as a pass/fail.